Once considered a symbol of progress; now the cause of a huge environmental problem: plastic. While cleaning up and recycling are great options for reducing plastic waste, the real breakthrough must come from innovation: a new type of plastic that is recyclable and easily degradable.

In 1907, Belgian-American Leo Baekeland made the first fully synthetic plastic from petroleum. Named after himself, bakelite did not conduct electricity and could withstand high temperatures. It was used for radios, telephones, kitchen utensils and toys. Years later, chemists invented new types of plastic which proved to be cheap, easy to make, and widely applicable. It was durable, water-resistent, and repelled odors. Certain plastics were seemingly unbreakable and to top it all off: plastic lasts forever. Who wouldn’t want plastic? However, the infinite lifespan of plastic would backfire on the planet like a boomerang. In the coming years, plastic waste would pop up everywhere and could hardly be broken down by nature. The once revolutionary plastic is now a symbol of pollution.

Let's take a deepdive into the subject: seven topical questions about the reduction of plastic.

How big is our plastic problem, really?

We should start with some disturbing news. Recent research by a team of Canadian and Dutch scientists shows that plastic particles have been found in human blood. The results were published in the journal Environmental International in March 2022. Blood of 22 anonymous donors was examined and polymers, the building block of plastic, were found in three-quarters of the donors.

The amount of plastic in the blood is minuscule, comparable to a teaspoon of polymers in 1,000 liters of water. Whether it is harmful to health is still unclear: further research is needed to find out. Although the sample is limited, it has been established for the first time that plastic has reached the top of the food chain: the human interior. The presence of polymers has been identified in animals before. The picture of a bird's stomach full of plastic waste symbolizes the enormous amount of pollution on earth. Whales are also known to die because they swallowed unbreakable plastic. On November 21, 2018, a dead sperm whale washed ashore in the east of Indonesia with nearly 7 kilograms of plastic in its stomach. The plastic waste consisted of 115 cups, 25 plastic bags, plastic bottles, two flip-flops and over 1,000 pieces of rope. The excess plastic in the oceans is not only dangerous when eaten by animals, it also causes birds, seals and turtles to become entangled in ropes and nets, with many dying as a result.

The mountain of plastic is immense. Every year, the world produces 380 million tons of plastic, according to data from Our World in Data. Most of the world's plastic disappears into landfills or is burned. Only a small portion is recycled, but fortunately that share is growing. The most plastic per capita is used in China, America and Europe. As prosperity grows, so does the use of plastic.

Not all plastic is collected and reused after use. Some 60% of all mismanaged plastic waste comes from East Asia and the Pacific. It also appears that economically disadvantaged countries place a relatively greater burden on the environment with plastic because there is no system for waste separation.

Of all the plastic produced, about 8 million tons disappear into the oceans each year. Due to ocean currents, plastic concentrates in five mega-drawing vents, called gyres, can cover an area of thousands of square kilometers. The first was discovered in 1997. We call these collection sites "plastic soup," a term widely used in the media, signifying plastic garbage dumps in the ocean. Two of these gyres can be found in the Atlantic Ocean, two in the Pacific Ocean and one in the Indian Ocean. On this map from PlasticAdrift you can see where all the plastic is floating.

How is the plastic problem being addressed?

Since the 1980s and 1990s, it gradually dawned on us that the success of plastic has a huge downside. In recent decades, numerous scientists and NGOs have worked hard to provide insight into the problem. In this decade, it is up to politicians and industry leaders to address the problem with measures and actions. There are four possible solutions. All four should contribute to less plastic pollution in the world.

1. Discourage the use of plastic

2. Clean up plastic waste

3. Prevent plastic from entering the environment

4. Make new plastic that is biodegradable and recyclable

How are we doing with discouraging the use of plastic?

Requests to consumers to use less plastic have had little effect. Most consumers like convenience and find alternative packaging complicated or expensive. Friendly appeals to businesses to use a little less plastic have also fallen on deaf ears: few businesses are willing to take cost-increasing measures for a better environment on their own, although the number has been growing in recent years. A more effective step to reduce plastic use is regulation, and governments are slowly but surely coming up with new measures. In Europe for example, a mandate banning the use of "single-use plastics" has been active since 2021. In the hospitality industry, during festivals and in offices, single-use plastic is prohibited for the foreseeable future: examples being coffee cups and straws. Instead alternatives that are sustainable and biodegradable should be used.

In the United States too, rules have been proclaimed to reduce the use of plastic. Bans on single-use plastic bags and straws take place at the city and state level. Eight states have now banned single-use plastic bags. You can find an overview of the current situation here. It is expected that the number of states moving to ban single-use products will grow.

How can we clean up our oceans?

Many millions of tons of plastic have flowed into our oceans in recent decades. And while some plastic will eventually break down into microparticles due to UV light exposure, a majority will not. In Europe, a young man named Boyan Slat has become well known for his focus on oceanic plastic soup. Slat created a foundation called Ocean Cleanup, which aims to pull plastic out of the water with large, floating plastic catchers. The group's stated mission is to clean up 90% of all floating plastic in the ocean.

The team behind Ocean Cleanup studies ocean currents in order to collect the debris in large, u-shaped screens. Ocean Cleanup also works to prevent large pieces of plastic from breaking down into harmful micro-particles. In addition, their focus is not only limited to oceans; the organization also cleans up rivers, which often carry plastic to the ocean. To attract attention to the cause and raise funding for the future, the group recently sold sunglasses created from garbage that was fished out of the ocean. Proceeds from this fundraiser will help eliminate 500,000 soccer fields worth of floating plastic.

Doubts are growing within the scientific community as to whether the plastic soup in our oceans actually contains all the plastic that has made its way into the ecosystem. Research is ongoing, but many scientists suspect that what is found in the gyres may be a fraction of all the plastic in our oceans. Researchers suspect that a significant portion may have broken down into microplastics, which inevitably sink to the ocean floor. Whether the bacteria that result can break down these polymers is unfortunately still unknown.

What about preventing plastic from entering the environment?

The best way to prevent plastic from entering the environment is to create a strong waste management system. Unfortunately, this is often the purview of more affluent countries; many nations do not have the resources to collect and recycle plastic.

As affluent nations that are also major consumers of plastic seek to solve this challenge, plastic recycling is also growing worldwide. To learn more, the research outlined on this data map illustrates the trend from 1980 to 2015.

If the trends outlined in the adjoining map were to extend to the year 2050, the incineration of plastic waste would fall at 50%, recycling at 44%, and discarded waste at 6%. While hopeful, researchers also say there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate that this will actually occur. In other words, government regulation and industry innovation are key to getting out of the plastic spiral.

With growing attention for real investment in recycling, processes are improving. One of the biggest challenges with recycling plastic is the mix of various materials in the waste stream, and the difficulties in separating different types of plastic. The end result is that only low-grade applications are currently possible from the recycled plastic mix, including waste bins, roadside berms and garden chairs.

A new technique is being developed to separate various types of plastic using a magnetic field to sort by weight. Heavy to light PET, polystyrene, polyethylene and polypropylene can be separated using the new technique. The Dutch company Umincorp has developed the technique and has a factory in Amsterdam. With the separated plastics, higher-quality packaging can be created for non-food and food products alike.

In March 2022, the international supermarket chain Albert Heijn was the first to use closed-loop recycling with plastic fruit trays made from PET extracted from household waste. Until then, this type of recycling had only been accomplished on a small scale, with PET bottles that were returned by consumers. With this technological breakthrough, the supermarket chain aims to strongly promote the use of recycled plastic. However, recycled PET is not biodegradable, and so can still wind up in landfills.

Additional promising techniques are also under development to sort various forms of plastics from waste streams. One example is Near Infrared Spectroscopy (NIR) which recognizes the chemical structure of plastic. Intelligent robotic arms are also being deployed to remove plastic objects from the environment, and are able to accomplish this task twice as fast as a human.

This recently published report outlines closing the plastics circularity gap and contains a detailed and comprehensive scientific analysis of the current state of plastic recycling. The report, authored by AFARA, IHS market and Google, identifies strategic interventions to optimize plastic recycling. These include improved inventory management at corporations, an increase in consumer education, a tax on virgin plastics, and better recycling systems, both mechanical and chemical. If all these interventions are adopted, it might be possible to collect and recycle a substantial portion of plastic waste by 2040. But to prevent plastic from entering the environment at all, a completely systemic overhaul is needed to transition from a linear economy to a fully circular one.

What is the current state of new bioplastics?

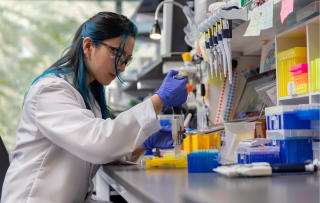

Innovation in the field of bioplastics shows promise. The ideal new plastic is created from biological material and is both recyclable and biodegradable. In San Jose, California, the company Full Cycle Bioplastics has developed a groundbreaking technique for this purpose.

Full Cycle's technology addresses three global issues – plastic pollution, food waste and climate change – by transforming organic waste into Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA). PHAs are a well-known family of bacteria based biodegradable plastics and offer an approach to carbon neutrality while supporting a more sustainable industry. In a recent interview with Fast Company, Dane Anderson, co-founder and CEO of Full Cycle, said "we're using one huge problem – the carbon emissions from food waste – to solve another, which is the global plastics problem, and petroleum plastics as a whole."

Full Cycle is unique in that it makes PHA out of food waste. And because food waste is a low-cost feedstock, the material produced as a result can be competitive with fossil-based plastics, the company says. Since food waste in a landfill emits methane, a potent greenhouse gas, the process can help eliminate those emissions and shrink the carbon footprint of the final product.

Another promising material is hydropol, which is made by Aquapak in Birmingham (UK). The company states that hydropol is fully biodegradable, nontoxic and safe for marine life. Hydropol is also water soluble, so the material grades in cold and hot water and can fully dissolve in minutes. Finally, it also serves as a barrier to grease, oil, and oxygen, so if hydropol is unintentionally released in the environment, it can safely biodegrade, according to Aquapak. Currently, the material is sold to packaging manufacturers who use it in a wide range of applications, including food waste bags, gloves and laundry bags.

In the Dutch city of Dordrecht, a demonstration factory that makes bioplastics from sewage sludge and wastewater is on the rise. A consortium has invested 2.5 million euros and wants to scale up to commercial production, once production from wastewater has been proven. Fatty acid-rich streams are used to feed the bacteria in the sludge that 'produce' the natural biopolymers; on a small scale, bioplastics have already been made this way, and hundreds of kilograms can be created in this factory. Future applications include soluble seedling trays and an agricultural film that can break down after being plowed under.

Additional possible raw materials for bioplastics include cornstarch and potato starch, but sugar cane and seaweed can also be utilized. Unfortunately, just because something is labeled 'bioplastic' doesn't necessarily mean that the substance is harmless to the environment. Bioplastics can also lack biodegradability, as they are chemically identical to 'ordinary' plastics and so are just as harmful to the environment. It's important for consumers to research the bioplastics they encounter in the marketplace.

What are the most promising solutions?

To start, all viable initiatives to protect the environment from plastic waste should be deployed. These include a ban on single-use plastics, cleaning up the plastic soup, increasing plastic recycling, and manufacturing bioplastics. However, given the practical benefits of plastic, it is unlikely that the product will completely disappear from our global economy. Hundreds of millions of tons of plastic will still be produced annually in the coming decades.

There is encouraging promise in the utilization of new techniques that can sort different types of plastic from waste streams. Waste can also form the basis for raw materials in a new product, thereby creating an increase in economic value and presenting opportunities to companies that focus on recycling.

Manufacturing degradable and recyclable bioplastics presents another opportunity. If these new products are priced competitively and consist of the same advantages as oil-based plastics, the market opportunity is significant. That said, the deployment of bioplastics is in its infancy. They're not yet produced on a large scale, but with increased attention and investments, a breakthrough in the next decade is not unthinkable.

It's tempting to compare the transition from synthetic plastic to bioplastic with innovation in the automotive industry. In 2009, Tesla entered the market with the electric Model-S, a sports sedan with a battery instead of a combustion engine. The auto industry declared Elon Musk crazy, and predicted his endeavor would lead to bankruptcy. Twelve years later, every car manufacturer in the world is building electric cars, and Tesla is one of the most valuable companies on the NYSE.

Will this be the road to bioplastics? We still don't know. At 380 million tons of plastic a year, the market is substantial. If governments continue to tighten their regulations and citizens are convinced of the need for alternatives, then new companies will have a chance to grow. The next decade will be crucial, and will demonstrate whether this pivot can be successful. Our fragile environment clearly suffers from our reliance on plastic; its high time for innovation and stricter rules.

|

More action: join the plastic pollution coalition. It is a global alliance of more than 1,200 organizations, businesses and thought leaders in 75 countries working toward a world free of plastic pollution and its toxic impact on humans, animals, waterways, oceans and the environment. |

Written by

Written by